How does one research?

For many of us, it is a daunting task that seems reserved only for those who look like they have an inherent talent for it. But that is not the case at all. Even for published researchers and our esteemed professors, the process has not been without its challenges.

The second installment of the “Online Convoes on the Birth of Research Ideas and Thesis Topics” was hosted via Zoom on 18 March 2021 to demystify and look at the more human side of the research process. Three seasoned researchers from the Faculty of Education (FEd) shared their own research journeys to fellow FEd faculty members and staff, UPOU Master’s and PhD students, and participants from senior high schools.

Research is Advocacy

The FEd Dean, Professor Ricardo Bagarinao was the first one to share his experiences during his Masters. He recounted how his research interests were actually born out of a personal encounter with it in 1991. A flash flood in Ormoc City gathered the lives of more than 8,000 people, including some of Prof. Bagarinao’s family. This prompted him to investigate its causes and led him to issues concerning the environment.

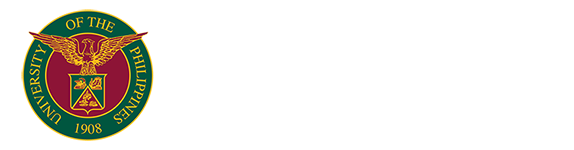

One’s advocacies, however, are not enough for a smooth transition to paper. Prof. Bagarinao mentioned how “cluttered” his initial efforts were as he tried to identify an interdisciplinary research topic required for his Master’s.

After scouring the literature, Prof. Bagarinao eventually decided to direct his research focus to emerging concepts in his field: watershed, landscape, and Geographic Information System (GIS) in relation to the environment. To learn more about these, he sought the news to identify his research problem. However, that resulted in even more possible topics.

“…medyo masakit na sa ulo kasi ang dami nang pumapasok na idea… Medyo nahirapan ako… Ang dami nang pumapasok na thoughts, ideas, at konsepto,”

He remedied this by creating a criteria so he could filter possible, and equally interesting, research topics systematically. For Prof. Bagarinao, a research topic should be:

- Simple (something that taps your strengths);

- Practical (something that can actually be done); and

- Relevant (something that is useful to wider society).

Selecting a research topic. Prof. Bagarinao suggests to filter all possible, and equally interesting, research topics through a criteria.

Looking forward, Prof. Bagarinao also wanted to identify a focus that will direct his future research so he can contribute to his advocacies. He shares his system of identifying below:

I think about <something> and ask, “what is needed [to be done] about this <something>?”

Guided by this system, Prof. Bagarinao thought about the problem of sea water intrusion in Cebu. He then thought that something had to be done about the impacts (health and, eventually, economical costs) of the sea water intrusion to marginalized populations in the area. Further, he identified the protection of the groundwater table as part of his proposed solution. These systematic reflections later solidified to a formal thesis:

Salinization of Aquifers and the Cost of its Damage and the Cost of Protecting the Groundwater Table in Cebu City.

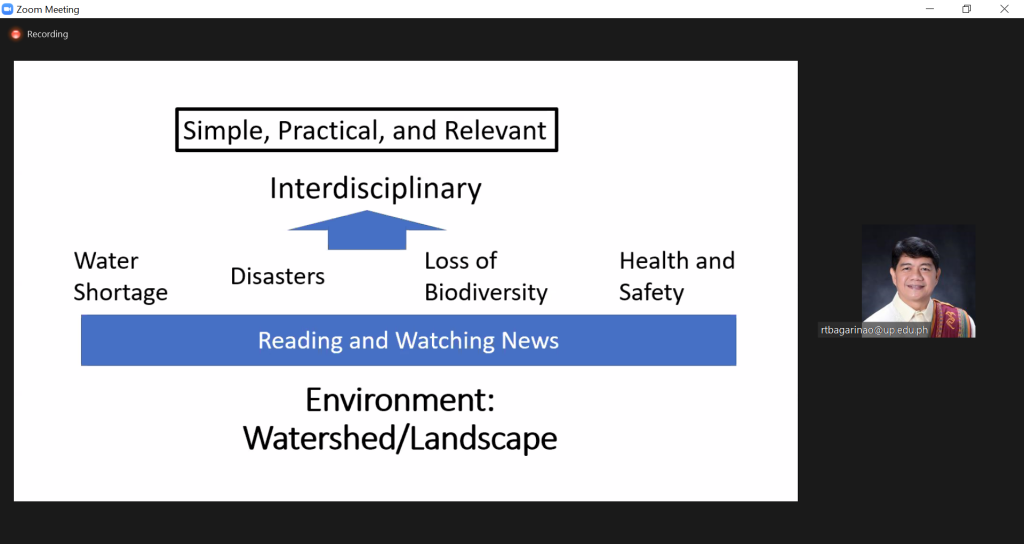

The second speaker and a PhD Environmental Science candidate at SESAM, UPLB, Mr. Jabez Flores, also opened his talk by introducing himself. His journey towards a Master’s and PhD did not start off in a straight path. After earning his bachelor’s degree in Sociology, he worked as a barista for 7 years at a local coffee shop for the joy of it. In the middle of his barista career, Flores began wondering where all the coffee he expertly brewed and food he served came from.

Paired with his environmentally conscious upbringing and experience of cancer in his family, he readily saw systemic problems in diet, health, and the environment. This genuine curiosity about food production, health, ecosystems, and the environment motivated him to pursue further studies. Flores enrolled in an Organic Agriculture course and later on pursued a Master’s degree in Environment and Natural Resources Management, both in the UP Open University.

Just three days after graduating from his Master’s, Flores took his first PhD class. He credits this eagerness to learn more to his pragmatic way of approaching research—solving his chosen problem and rallying his advocacy. Since then, his interest, stemming from organic agriculture and public health and nutrition, eventually led to his research on permaculture design.

Where did the food come from? PhD candidate Jabez Flores’s shares how his research pursuits are motivated by genuine curiosity and pragmatic ends.

In coming up with his research topic, Flores notes,

“…It didn’t just occur to me in one instance. It was a long and gradual process,”

—technically, a result of his many encounters with the literature, researchers, stakeholders, and himself.

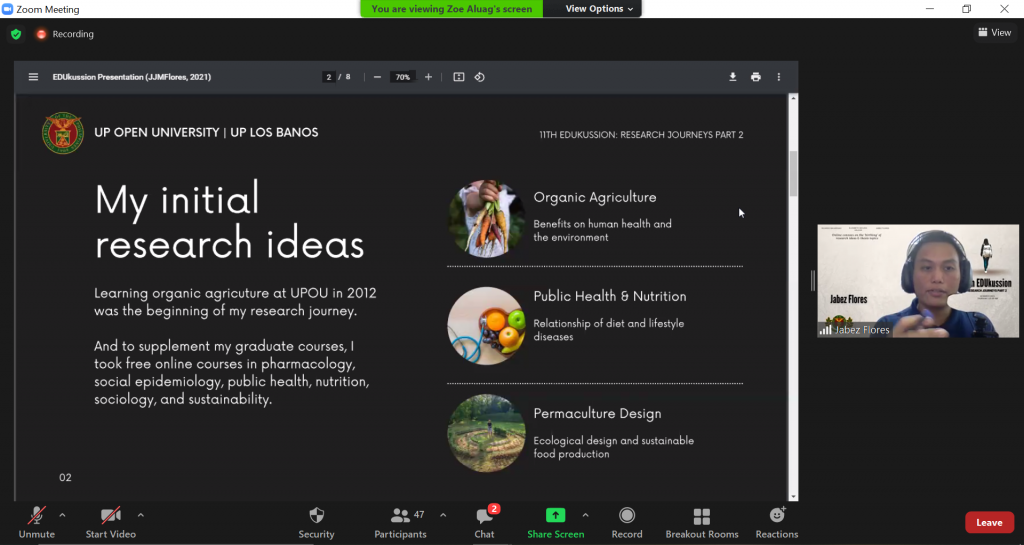

Agreeing to this is Assistant Professor J Aleta Villanueva, the Program Chair of the Diploma and Master of Social Studies Education (D/MSSE) and the FEd Faculty Secretary. She shared that her successful attempt at her PhD research topic was a product of a journey filled with its fair share of rejections and reflections.

“…It’s really years of identifying yung mga interests ko,”

Asst. Prof. Villanueva recounted that her extensive experiences in basic education and distance learning fueled her research interests in K-12 pedagogy and practice, blended learning, and learning community. The interactions of these experiences concretized these research areas into a coherent PhD v.2.0: Investigating Experiences and Outcomes in K-12 Blended Learning Classes through the Community of Inquiry Framework.

Researcher’s funnel. Asst. Prof. Aleta recounts how it took her several tries before she was able to pinpoint the main areas of study from which her dissertation topic will take form.

Despite bumps in the road, Asst. Prof. Aleta pushed through so she can earn her place in UPOU and serve her students and the Filipino people better. She adds that beyond the rewards of research, one should also be prepared to take on its consequent responsibilities,

“...for us to share and not be selfish of what we know…to continue to inspire each other in our pursuits,”

Research is Detective Work

One does not simply review the related literature (RRL)—a view shared by all three speakers.

Prof. Bagarinao shared that he uses relevant keywords when searching for related literature. He then judges each journal article based on its abstract. Here, what matters most is that you understand the abstract and see its relevance to your study.

“…pinipili ko lang yung mga abstract na naiintindihan ko,”

Prof. Bagarinao also searches the References section of an article he liked to find more related studies. Both he and Asst. Prof. Aleta noted that the RRL helps in establishing the novelty and relevance of one’s research as it is during this step in the process that knowledge gaps become apparent. According to Asst. Prof. Aleta, this section of the paper should go beyond describing studies done in a field. The RRL is where the researcher identifies, organizes, and argues.

She further advises that aside from the findings of a study, the methods and models used should also be reviewed to guide one’s design of the research implementation.

Thinking about the RRL. Asst. Prof. Aleta discusses some points to consider in going about the RRL. Source: D.C.F. Eacersall (personal communication, July 7, 2017).

In Flores’s case, he uses the RRL to justify the need for permaculture design to be explored and prove its place in Philippine agriculture and environment. He had to face rejections from his PhD adviser and wait for a few years before the literature was enough to be properly studied. Flores was able to take these challenges head on because he saw research as, essentially, detective work.

After reviewing what is known about a topic or a field of study, the next challenge is to write it. Flores shares how he structures this section of his paper in three steps:

- Present what is known about the topic/field;

- Present studies that support or challenge this knowledge; and

- Present your ‘but,’ your argument or challenge to the body of existing knowledge.

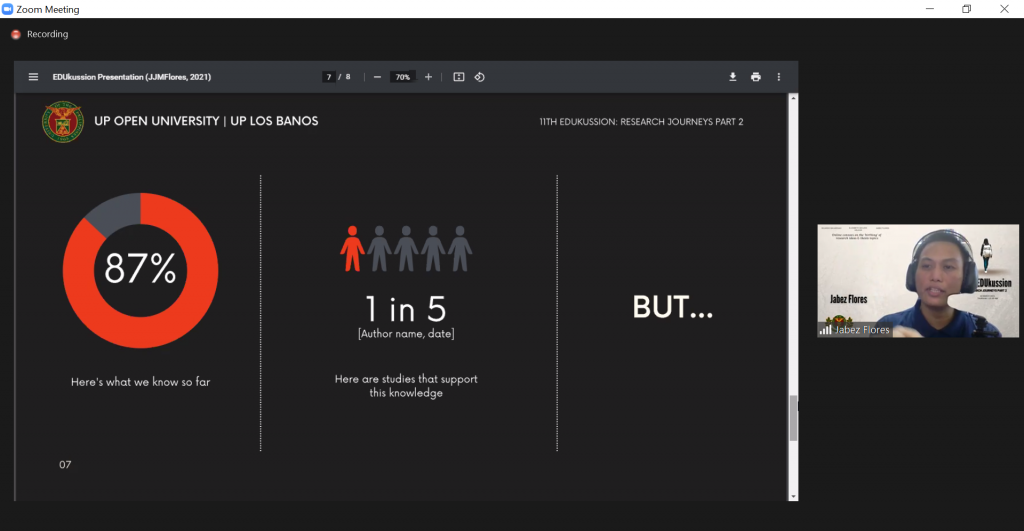

Writing the RRL. PhD candidate Jabez Flores shares his 3-step formula in writing the review of related literature.

A few more tips

The speakers provided some best practices of their own to help everyone in their research processes:

- Identify your problem first, and then figure out how your field of study can address it;

- Identify gaps in existing knowledge. You never really run out of it;

- Network with peers and other researchers through available platforms (e.g. ResearchGate);

- Create an outline to see themes and categories better. Revise as you see fit; and

- Empty your mind without judgement. Write it down. Journal. Record. Doodle. Draw. Blog (just look at Flores’ and Asst. Prof. Aleta’s own blogs).

Research is a Personal Journey

We probably have been introduced to the research process from a university lecture, where we religiously jotted down a diagram presented by our professors. However, we have to remember that despite the straightforwardness of such diagrams, the research process is an idiosyncratic enterprise (i.e., it differs from researcher to researcher). Our speakers showed us just that.

In his closing remarks, Flores noted that as researchers, we must “expect hardships”. To endure it, our speakers invite us to enjoy the process, the journey, and proactively learn about our fields and ourselves. With this, we are reminded that the researcher is, foremost, a human being. The speakers agree: to make good research, it has to matter to you and must meet a significant need in the world. Like how everyone started with an introduction of themselves, it is evident that one’s research is tied to oneself.

So, to know how to research, perhaps one must look in the mirror and ask.

Written by SPManrilla